Clients often ask about what happens to their estate (or someone else’s estate) if they die without a will in place. It is a question that I am generally happy to discuss, as it helps underscore why having a will is so important. With a will, you get to decide what happens with your estate, who looks after it, and who receives it. If you die without a will, legislation comes into action and makes these decisions for you. Of particular interest is the process by which the beneficiaries of the estate are determined through the concept of “next of kin” and the degrees of consanguinity.

Intestacy

Dying without a will is referred to as dying “intestate”. An intestacy is the result of having no valid will at the time of your death. On an intestacy, Part II of the Succession Law Reform Act (the “SLRA”) takes over and dictates who will receive the estate.

The short version is that if you die with a spouse and no issue (meaning your children and the descendants of your children), your spouse gets it all. If you die with a spouse and issue, there is a mechanism for determining their respective shares. If you die with issue but no spouse, your issue divides your estate (there is some potential complexity in this, but I will leave that for another post.)

Often, the above scenarios are what the client would intend and seem inoffensive enough. Though of course there are those who would rather their children (or grandchildren, etc.) not all receive an equal share for many reasons. In my experience, however, clients are surprised to learn what follows.

Consanguinity

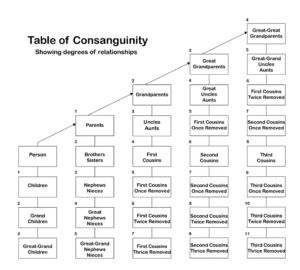

Who inherits where there is no spouse and no issue is determined by reference to consanguinity – a word derived from Latin meaning, roughly, closeness of blood. Consanguinity is measured by “degrees” and is usually visualized as a table showing how these degrees connect relatives.[i]

Under the SLRA, where there are no spouse or issue, the next to receive the estate of an intestate person are, in order: parents, siblings, nieces and nephews, and then “next of kin”. In the event that the intestate person died with none of the listed relatives surviving them, we turn to the table of consanguinity to determine just who the “next of kin” is. This is done by first going “up” the degrees of the table (tracing backwards in time through the ancestors of the deceased) and then “down” by degrees (to the closest living relative who is the issue of that ancestor) to find the “next of kin”, which may be an individual or a class of relatives (e.g. first cousins). The result is that, for example, a grandparent would inherit in priority to an aunt or uncle, and a great-grandparent in priority to a first cousin.

Only where there is no identifiable next of kin will the estate of the intestate “escheat” and become the property of the Crown.

Who Counts

This slightly antique area law has evolved over time to (attempt to) keep pace with changing social and familial norms. For example, “half-blood” relatives are counted equally as “full-blood” relatives; adopted children are considered to be the consanguineous descendants of their adoptive parents; and as of 2016, relatives who are conceived posthumously can be included (in certain circumstances.)

Notably, relatives by marriage are not connected by the degrees of consanguinity. Only those who can trace their connection to a common ancestor, regardless of marital status within the family, are counted.

Implications

There are some key assumptions that are reflected in this statutory scheme:

- People prefer to benefit their (blood) family;

- People prefer to benefit their closer relatives to the exclusion of their more distant ones;

- Spouses are a special case, and considered closest of all, despite not being related by blood;

- Spouses of family don’t rank;

- Children, and further issue, should be provided for;

- Beyond a few exceptions, older relatives take priority

- All relatives of the same degree of kinship are entitled to an equal share.

Many clients share many of these assumptions in their own estate planning, the first five in particular. However, the last two, which would enable a parent to inherit over a sibling, and for all nieces and nephews to receive an equal share of an estate, often don’t sit well with clients. Either they seem impractical and unnecessary (benefiting an older relative is rare), or they don’t reflect the reality of most families.

Estate planning is an inherently personal thing. A legislative answer, given in the absence of effective estate planning, is by necessity an attempt at a one-size-fits-all solution. In this case, one derived from ancient notions of blood and kinship. As it is written, the law rarely matches up well with clients’ individual circumstances. As a result, the best advice – as always – is to plan ahead.

For assistance with estate planning, trust planning, or cross-border planning, contact the estate lawyers at Mills & Mills LLP at 416-863-0125 or send us an email.

[i] Consanguinity had its first applications in determining who one could marry. Under Roman civil law, you were forbidden to marry someone within four degrees. Centuries later, under Catholic law this was raised to seven degrees. As with so many things, the rampant inbreeding of Medieval European nobility got in the way, and changes were needed. Because the prohibition on marriages within seven degrees “cannot now generally be observed… without grave harm…” (according to the Fourth Lateran Council) it was switched back to four degrees, and the mechanism for counting degrees was restored to widen the pool of suitable spouses. This allowed for marriages between cousins, and in due course, aristocratic hemophilia.

2 St Clair Ave West

2 St Clair Ave West